Drink When Thirsty debunks the many myths about hydration and dehydration like “If you are thirsty, it’s already too late” and “If your urine is yellow, you are dehydrated.” This article suggests that Drink When Thirsty is the best and healthiest strategy for hydration during exercise.

| It turns out that your body’s natural, thirst mechanism (700 million years old) works well to keep you hydrated and healthy during exercise. In fact, the amount of water your body requires is probably far less than what the Sports Drink and Bottled Water companies have been telling us. |

People may be drinking too much water…

With all the hype about the risks of dehydration, it is actually over hydration (hyponatremia) that may be more of a risk. People are now having serious health problems from over hydration for endurance races and even hiking in the Grand Canyon—sometimes resulting in death1,2,3. [Note: Since I first published this post it has been shared by numerous Emergency Medical Treatment and Search and Rescue organizations for this very reason.]

Learn more about choosing between our favorite backcountry filters – Sawyer Squeeze vs Katadyn BeFree vs Platypus Quickdraw and hiking water bottles.

You make Adventure Alan & Co possible. When purchasing through links on our site, we may earn an affiliate commission at no additional cost to you. Here’s why you can trust us.

Best Hydration and Purification System – It’s NOT Complicated!

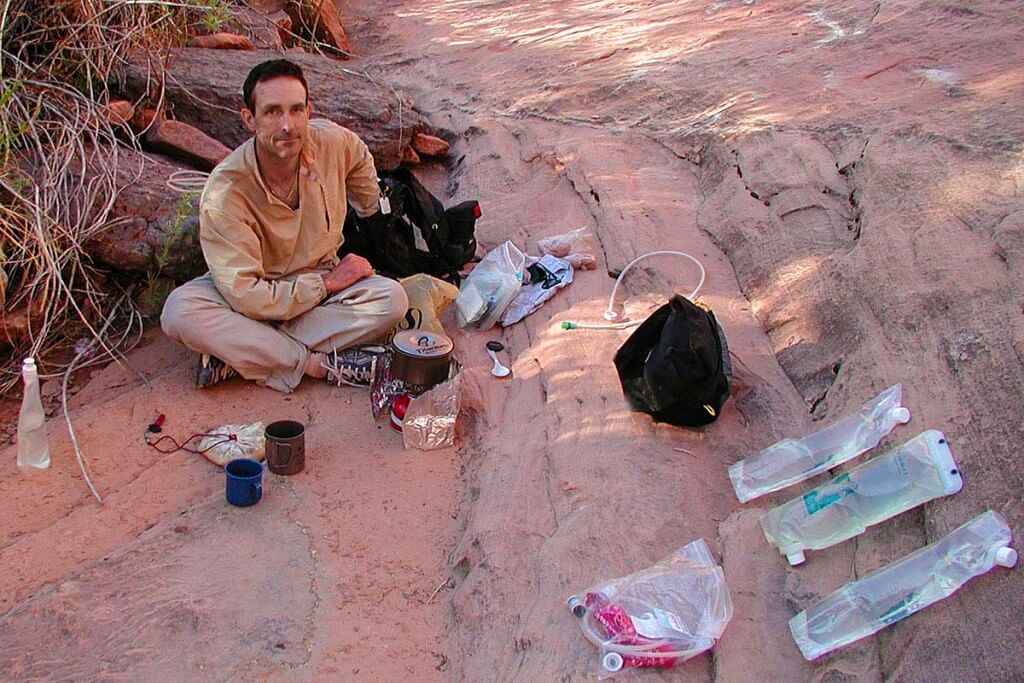

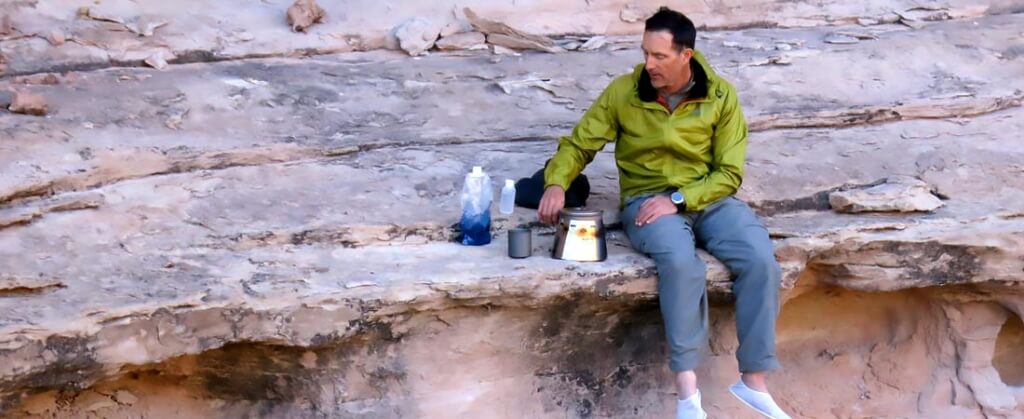

The simple, inexpensive Hydration and Purification System that Alison and use is shown above. When “drinking to thirst,” it has kept us well hydrated — even between distant water sources in the desert.

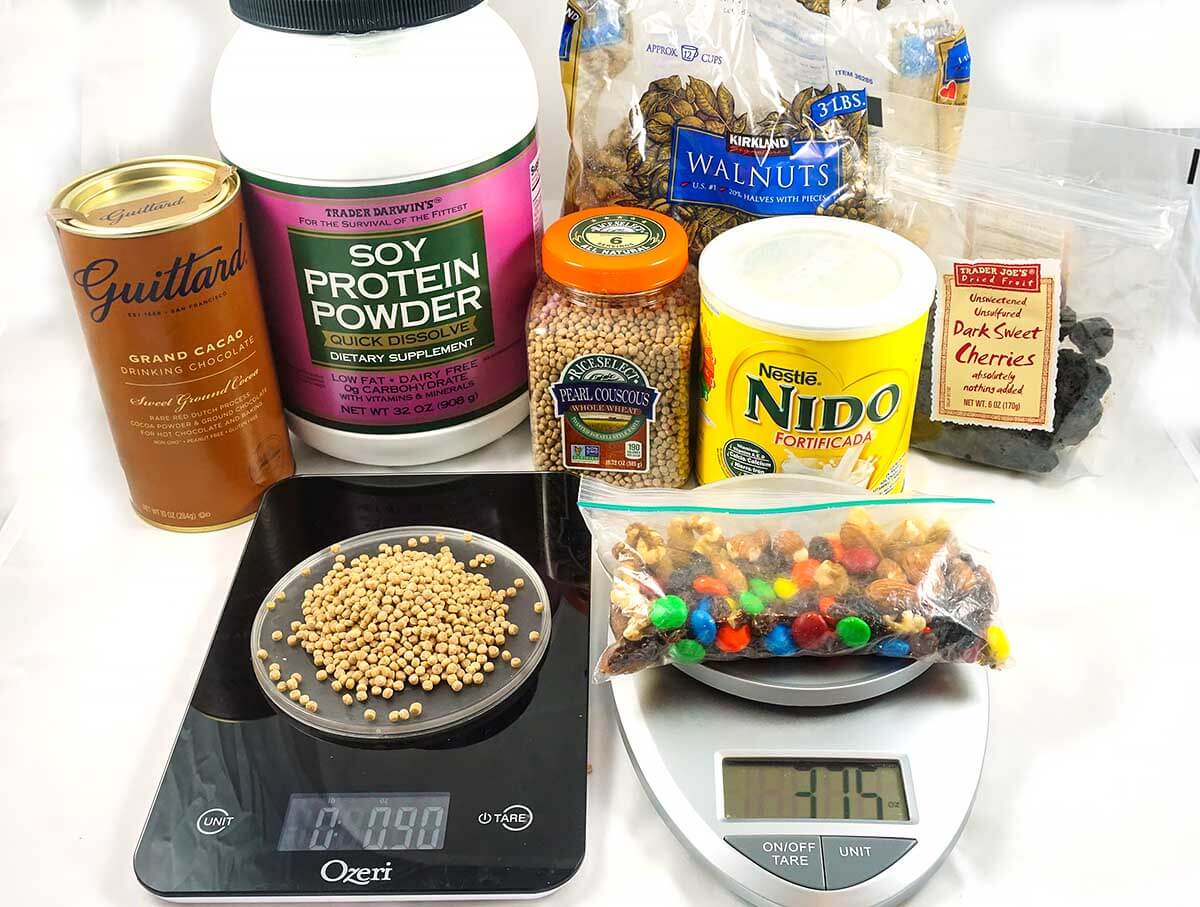

Excerpted from my 9 Pound – Full Comfort – Lightweight Backpacking Gear List:

- Sawyer Squeeze Filter: We can drink immediately at water sources. This means both quick, effective hydration and less water to carry when we hike.

- Water Treatment Tablets: For fast, efficient water purification in camp. We can treat 3 or more liters of water in less than a minute. And it’s ready to drink 20-30 minutes later.

Drink When Thirsty – Myths and Facts about Hydration

I recently interviewed three world experts in the field of sports hydration (not affiliated with Sports Drink and Bottled Water companies)

- Dr. Marty Hoffman, MD, founding member of the Foundation for Medicine & Science in Ultra-Endurance Sports, a member of the Wilderness Medical Society, and professor at the University of California Davis

- Dr Tamara , D.P.M., Ph.D., Associate Professor of Exercise Science, Oakland University, Rochester, MI

- Dr. Kristin Stuempfle Ph.D, Professor, Health Sciences, Gettysburg College

This is what I learned from these experts…

Myth1 – If you are thirsty, it’s already too late

Correct – Drink When Thirsty

- All the experts in sports hydration I talked with adamantly agreed that Drink When Thirsty is the best and healthiest strategy for hydration during exercise*.

- As Dr. Hoffman’s puts it: “Drink When Thirsty works for prolonged exercise. Our bodies have a fine tuned feedback system that lets us know when to drink…there is no real danger of dehydration when people have access to water. Thirst kicks in, and people drink.”

- This agrees with the recommendation from the Statement of the Third International Exercise-Associated Hyponatremia Consensus Development Conference, 20154 to Drink When Thirsty; “Using the innate thirst mechanism to guide fluid consumption is a strategy that should limit drinking in excess and developing hyponatremia [over-hydration with significant health consequences] while providing sufficient fluid to prevent excessive dehydration.”

- Excessive drinking when you are not thirsty increases the risk of hyponatremia, arguably a greater risk than dehydration.

*Dr. Tamara Hew-Butler says the natural thirst mechanism has been working in animals and keeping them well-hydrated for at least 700 million years. See more from Dr. Hew on how the human thirst mechanism works.

So why have we been told to drink, drink, drink?

Why do we continue to hear sayings like, “hydrate or die,” “if you are thirsty, it’s already too late,” and stating that “your athletic performance will drop if you don’t drink enough“?

Deborah Cohen, investigations editor for the BMJ [formerly British Medical Journal], wrote up her findings in the 2012 feature article, “The truth about sports drinks5“. This article implies that the sports drinks industry has dramatically increased sales of their products by:

- Creating a “disease of dehydration”

- Stating that the natural thirst mechanism is inadequate to keep athletes hydrated. [Cohen implies that the evidence for this view is lacking.]

- And that this “lack of evidence” is in part due to the close financial and other affiliations between the sports drink companies and the scientists/researchers and supporting institutions that produce the research to support this view.

- Cohen’s article gives examples of studies supporting the sport drink companies claims, that when reviewed by an independent panel of experts, are not deemed robust enough to support those claims.

Here are some excerpts from the article

“Sports drinks are increasingly regarded as an essential adjunct for anyone doing exercise, but the evidence for this view is lacking. Deborah Cohen investigates the links between the sports drinks industry [e.g. Powerade (Coca-Cola) and Gatoraide (PepsiCo)] and academia that have helped market the science of hydration.”

‘“The problem was industry wanted to sell more products so it had to say that thirst was not adequate,” Noakes [Professor Tim Noakes, Discovery health chair of exercise and sports science at Cape Town University] says.’

| ‘Disease mongering is a well documented phenomenon in healthcare6 and Noakes suggests that industry has followed a similar pattern with dehydration and exercise.

“When industry wanted to sell more product it had to develop a new disease that would encourage people to overdrink,” he said adding: “Here’s a disease that you will get if you run. Here’s a product that is going to save your life. That’s exactly what they did. They said dehydration is a dreaded disease of exercise.”’ |

Debunking Other Hydration Myths

The following debunks:

- You need to drink a liter per hour

- Dehydration is a big problem

- If your urine is yellow you are dehydrated

- Dehydration causes cramping

And finally it address the Big Question, “How much water should I drink/carry on a hike?”

Myth2 – You need to drink a liter per hour

Correct – Drink When Thirsty

- Again, Drink When Thirsty is the best strategy.

- Dr. Kristin Stuempfle says that studies7 show that the human body can only process a maximum of 0.8 liters (27 oz) to 1 liter (34 oz) of water at rest. That is not what your body needs—just the maximum amount of water it can process if needed—an important distinction.

- That maximum amount of water processed will go down during exercise. According to Dr. Stuempfle our body’s natural response to exercise is to shunt blood from the kidneys and the GI (stomach and intestines) and put it toward motor (leg) muscles, heart, and skin (cooling). In addition, during exercise the body secrets a natural antidiuretic hormone (ADH) to slow urine output. All these combine to reduce your body’s ability to process water.

- So if you drink more water than you need during exercise (i.e. not drinking to thirst) then your body is receiving more fluids but has less capacity to handle them. Thus the risk of overhydration, and possibly hyponatremia.

In cooler environments where water is plentiful you may not need to carry any water with you. Drink from the source, and you will likely not be thirsty when you reach your next water source.

Myth 4 – Dehydration is a big problem

Correct – Mild dehydration is not a cause for serious concern

- It will not significantly impair performance or health

- Dr Hoffman told me: “Even a mild hydration deficit of 2-3 liters is OK (provided you were adequately hydrated at the start of your hike). You may not be happy about it, but it’s not a serious problem.“

- Dr Hoffman also told me: “Top ultra runners are still performing well late in the race [100 miles] with a few percent bodyweight loss. They could not perform as well as they do, if percent bodyweight loss and mild dehydration was a big impediment to race performance8,9.”

Myth 5 – If your urine is yellow you are dehydrated

Correct- Urine naturally turns yellow during exercise, even when adequately hydrated

- Dr Hoffman says that: “Trying to keep urine clear during exercise will cause over hydration.” There was complete agreement among all the researchers on this point.

- Additionally Dr Hoffman said: “[during exercise] urine color is not useful, and should not be used, as an indicator of hydration status…During exercise, because of hormonal influences to retain fluid and blood flow being shunted away from the kidney, urine production should be diminished, so urine color will darken.”

- And from Cohen’s article5: “The science of dehydration has led to another widely held belief that is not based on robust evidence—that the colour of urine is a good guide to hydration levels.” And also from Cohen’s article5: “There is a lack evidence for the widely recommended practice of assessing hydration status by looking at the colour of urine,” it suggests.

Myth 6 – Dehydration causes cramping

Correct – Cramping well understood but not likely from dehydration or electrolyte levels

- All the researchers I spoke with agreed that cramping is complex, not well understood and likely has multiple causes.

- They also agree that dehydration and electrolyte depletion are not likely the main causes.

- Dr. Hoffman not only noted that cramping appears to be neuromuscular, but that dehydration or electrolyte depletion does not cause cramping. Dr. Hoffman said this finding has been known for a number of years. In fact, cramping has more to do with neuromuscular nerve misfiring—nerves sending a false signal to muscles to contract and stay contracted, as indicated in research10 by Martin P Schwellnus, UCT/MRC, Research Unit for Exercise, Science and Sports Medicine, Department of Human Biology, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Cape Town, South Africa.

- From the New York Times Article A Long-Running Mystery, the Common Cramp by By GINA KOLATAFEB. 14, 2008:

- “DR. SCHWELLNUS proposes that the real cause of cramping is an imbalance between nerve signals that excite a muscle and those that inhibit its contractions. And that imbalance, he said, occurs when a muscle is growing fatigued.”

- “There’s the dehydration proposal: you just need more fluid. But, Dr. Schwellnus said, he studied athletes who cramped and found that they were no more dehydrated before or after a race than those who did not have cramps.”

How much water should I Drink/Carry on a hike?

This is the big challenge for backpackers, day-hikers or others that need to carry enough water between distant sources. Unlike Dr. Hoffman’s “There is no real danger of dehydration when people have access to water,” there is a possibility that if we don’t carry enough water between distant sources that we could run out of water and potentially become dehydrated. On the other hand, if we are hiking a long distance between water sources and and decide to carry 5 liters of water we are carrying an additional 11 pounds. This too has serious downsides.

So the big question for hikers and backpckers is

How do you estimate the “right” amount of water to carry between distant sources? |

The goal is homeostasis, or to drink the same amount of water as your body uses. But how do we estimate our personal water consumption needs for homeostasis in the field? There is likely no “right or exact” answer to this. Dr. Stuempfle and Dr. Tamara Hew-Butler agree that the following would be a reasonable strategy for individuals to estimate their personal water consumption in the field:

- On test day-hikes (or a weekend backpacking trip), Drink When Thirsty and record the amount of water your drink per hour. Try to do this close to the same level of exertion, and temperature and humidity that you will expect on your backpacking trips (or long day hikes).

- Use this consumption rate per hour as a starting point for estimating the amount of water you’ll need to carry between distant sources in the field for your longer and more serious trips.

- It is best to be conservative (carry a bit more water) until you have tested out and fine tuned your personal water consumption rate over at lest a few longer trips in the field.

- Obviously if it is hotter, more humid, you are working harder, or your pack is heavier, you may need more water per hour. But, if it is cooler, less humid, or you are not working as hard, you may need less water per hour.

On a personal note, when following Drink When Thirsty I frequently do not carry any water with me in the field (Sierras, Appalachian Trail, etc.). When I drink (using aSawyer Squeeze Filter so I can drink directly at the source), I find that I am unlikely to be thirsty until I reach the next water source. My wife seems to run a bit thirster, and in addition to drinking at water sources, she usually carries somewhere between ½ to ¾ of a liter between sources.

Although I rarely carry water with me, the desert is the exception. This picture is from a drought year in the Southern Utah desert. So an unusually dry time in an already hot and dry place. I have collected a lot of water: for dinner that evening, breakfast the next morning & to carry during the day to our next reliable water source.

The only place we carry large amounts of water between sources is in the Desert Southwest, like Canyoneering in Utah. But even then, following Drink When Thirsty, we carry less water than the “recommended” amounts in guide books and other “authoritative” sources. We pull long days in the desert and feel healthy and fine. But we have years of field experience and comfortably know our personal water needs in the desert.

How the natural thirst mechanism works

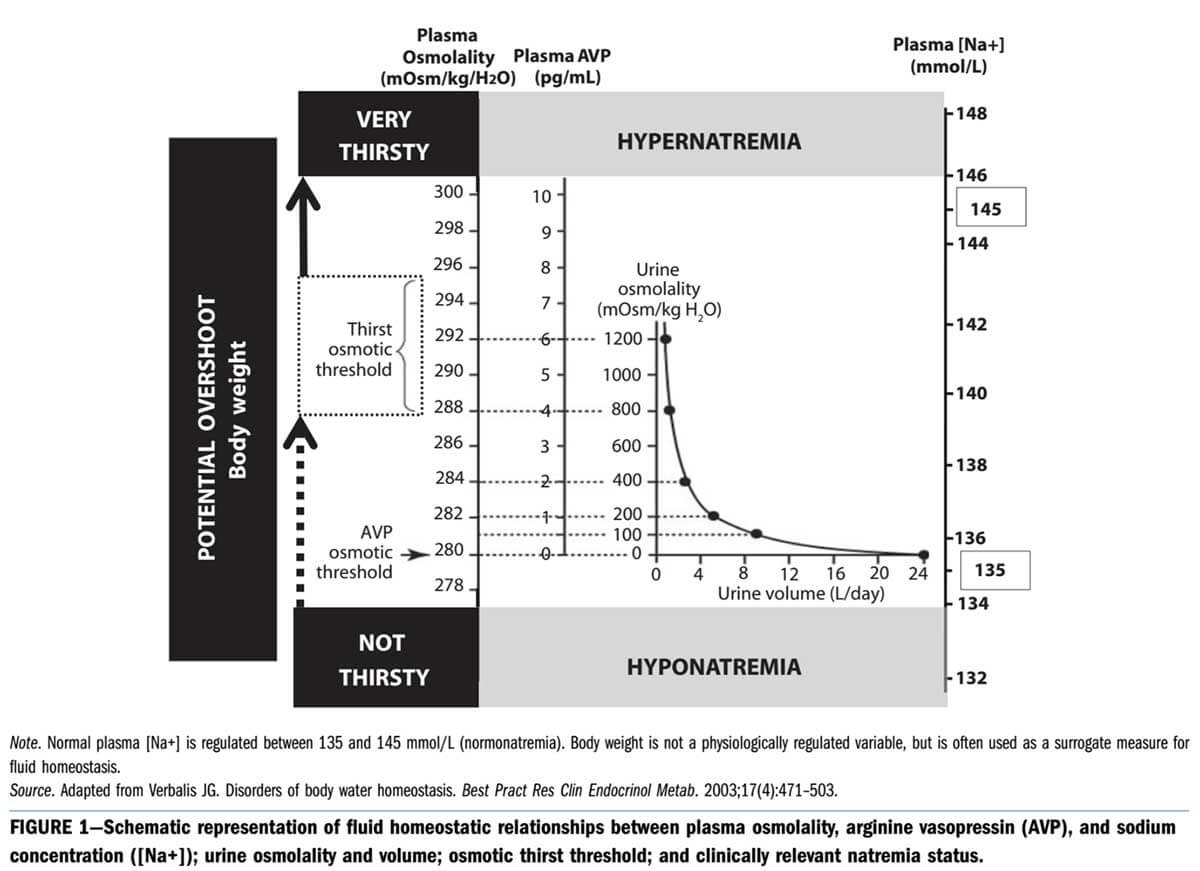

Dr Tamara Hew-Butler, who has studied the natural thirst mechanism in animals, says it’s been working to keep them well-hydrated for at least 700 million years. The human thirst mechanism functions in two ways:

- Brain sensing electrolyte levels11: Your brain has real-time osmosensors that monitor sodium concentrations (more specifically, the amount of osmoles, for which sodium makes up the greatest amount) circulating in the blood. When sodium levels start to rise above normal, your body has a two stage response. The first response, is to slow urine output and therefore water loss (this occurs before thirst is triggered). If sodium levels continue to rise, your thirst mechanism kicks in and you become thirsty. It is important to note that you are NOT dehydrated at this point. All this happens before dehydration becomes an issue. This is your body’s normal mechanism to keep you from getting dehydrated. Dr. Hoffman and Dr. Hew-Butler both point out that as long as folks have access to water, their thirst will cause them to drink and not become dehydrated.

- Your heart (actually the main valves) senses blood volume (water): Your heart valves have barorreceptors that can detect a reduction in blood volume (water in the body). This also has a two stage response just the same as the brain’s osmosensor responses. Stage 1 happens at an 8-10% blood volume depletion and triggers an anti-diuretic hormone release which slows urine output and therefore water loss. You are not thirsty at this point. If blood volume continues to decrease, your thirst mechanism kicks and you get thirsty. Again note: that you are NOT dehydrated at this point. All this happens before dehydration become an issue. This is your body’s normal mechanism to keep you from getting dehydrated.

Figure source: 11 – INADEQUATE HYDRATION OR NORMAL BODY FLUID HOMEOSTASIS? – Tamara Hew-Butler, PhD, LETTERS, American Journal of Public Health, October 2015, Vol 105, No. 10, page e6

Summary

Drink When Thirsty, it’s been keeping hominoids well hydrated for millions of years.

References

1 Three Cases of Severe Hyponatremia During a River Run in Grand Canyon National Park – Emily A. Pearce, BS, et al., WILDERNESS & ENVIRONMENTAL MEDICINE, 26, 189–195 (2015)

2 Hiker Fatality From Severe Hyponatremia in Grand Canyon National Park – Thomas M. Myers, MD, et al., WILDERNESS & ENVIRONMENTAL MEDICINE, (2015)

3 Exercise-associated hyponatremia with exertional rhabdomyolysis: importance of proper treatment – Martin D. Hoffman1, et al., Clinical Nephrology, DOI 10.5414/CN108233

4 Statement of the Third International Exercise-Associated Hyponatremia Consensus Development Conference, Carlsbad, California, 2015 – Hew-Butler, Tamara DPM, PhD, et al., Clinical Journal of Sport Medicine: July 2015 – Volume 25 – Issue 4 – p 303–320, doi: 10.1097/JSM.0000000000000221

5 The truth about sports drinks – Deborah Cohen investigations editor, BMJ 2012;345:e4737 doi: 10.1136/bmj.e4737 (Published 18 July 2012)

6 Moynihan R, Heath I, Henry D. Selling sickness: the pharmaceutical industry and disease mongering. BMJ 2002;324:886.

7 Peak rates of diuresis in healthy humans during oral fluid overload – Noakes TD, et al., 2001 Oct;91(10):852-7. PMID:11732457

8 Race Diet of Finishers and Non-Finishers in a 100 Mile (161 km) Mountain Footrace – Kristin J. Stuempfle, PhD, Martin D. Hoffman, MD, Journal of the American College of Nutrition, Vol. 30, No. 6, 529–535 (2011) page 529

9 Association of Gastrointestinal Distress in Ultramarathoners With Race Diet – Kristin J. Stuempfle, Martin D. Hoffman, and Tamara Hew-Butler, International Journal of Sport Nutrition and Exercise Metabolism, 2013, 23, 103 -109

10 Cause of Exercise Associated Muscle Cramps (EAMC) — altered neuromuscular control, dehydration or electrolyte depletion? M P Schwellnus, British Journal of Sports Medicine 2009 43: 401-408 originally published online November 3, 2008 doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2008.050401

11 INADEQUATE HYDRATION OR NORMAL BODY FLUID HOMEOSTASIS? – Tamara Hew-Butler, PhD, LETTERS, American Journal of Public Health, October 2015, Vol 105, No. 10, page e5

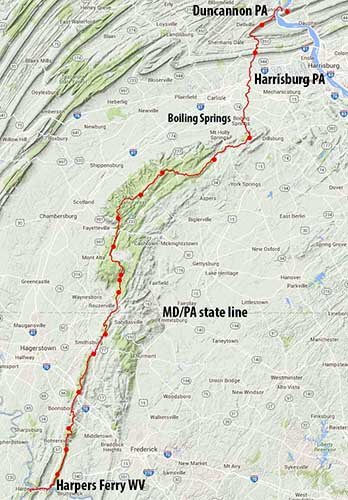

Light pack & easy hiking: Dawn view across the Appalachian ridge from White Rock Cliffs of South Mountain.

Light pack & easy hiking: Dawn view across the Appalachian ridge from White Rock Cliffs of South Mountain.