Best Lyme and Zika Prevention for Hiking

2018 is forecast to be the worst year for tick/Lyme disease*. But don’t let fear of Lyme or Zika keep you off the trail! This article has tips on the clothing, gear, repellents, and techniques that will maximize your Lyme and Zika Prevention as well as other tick/insect diseases when hiking or backpacking. Includes section on new Picaridin lotion which is more effective than DEET with none of the downsides.

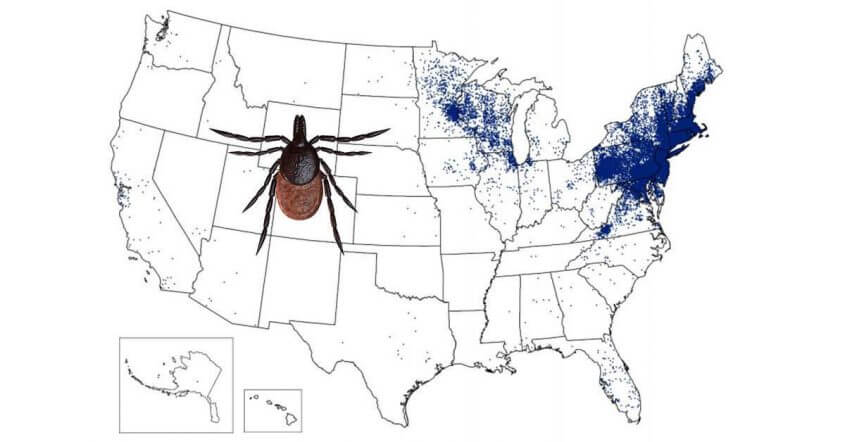

Lead photo: 2015 map of prevalence of Lyme disease [source US Centers for Disease Control (CDC)]. Superimposed on the map is a blacklegged tick, the primary transmitter of Lyme disease to people. Zika is also on the increase as noted here (CDC Map of Zika), and here Harvard Medical School Article on the rise of Zika.

This Article in Five Parts

- DON’T GET BIT – DON’T GET SICK: Why not getting bit is your first and best strategy for lyme and zika prevention.

- Best Ways to Protect Yourself from Lyme & Zika While Hiking: The Cliff Notes version

- New Picaridin Lotion. More effective than DEET with none of the downsides!

- What to Do if You Get a Tick Bite

- Non Chemical Ways to Reduce Bug Bites: For those leery of chemicals. But this content improves the effectiveness of all methods to reduce bug bites, chemical and non-chemical.

Why it’s hard to check for ticks in the field: Blacklegged tick nymphs which can transmit Lyme disease (second from left in photo) are exceptionally hard to see in the field. It’s extremely difficult to find them on your body during an evening check in camp and showering is not usually an option. For instance, how would you find the second from left blacklegged tick on your scalp or in body hair? Keeping them off of your body in the first place is your best strategy. BUT! by all means, continue to check for ticks (just don’t expect it to be 100% effective in the field). AND if you remove a tick quickly (within 24 hours) you can greatly reduce your chances of getting Lyme disease.

1. Don’t Get Bit – Don’t Get Sick

The best strategy to reduce your risk of getting a bug-transmitted diseases like Lyme and Zika is to not get bit in the first place. I know this sounds obvious, but some bug-transmitted diseases are not preventable. That is, if you get bit by a bug carrying some diseases you may get infected despite the best medicine. And if you contract a disease there may be no medications to effectively treat it. Consider the following:

- Lyme Disease: Currently, there are no vaccines to prevent tick-carried diseases like Lyme disease, or Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever. Fortunately per the CDC, “patients treated… in the early stages of Lyme disease usually recover rapidly and completely.” (But note: there is some controversy about the effectiveness of treating Lyme disease if undetected/not-treated in time.)

- Zika & West Nile: There are no vaccines to prevent mosquito-carried diseases such as Zika, and West Nile encephalitis today. And there are “no specific medicines” for Zika or West Nile if you contract them.

2. Best Lyme and Zika Prevention for Hiking

| Permethrin Treated Clothing Per the CDC a key element for maximum tick and mosquito protection is wearing Permethrin-treated clothing. Treated clothing can be of thinner, cooler fabrics and still provide protection. This is crucial to staying cool and comfortable when hiking in warm weather—the conditions when bugs are prevalent & disease most likely. |

The following is SAFE and effective. The “Best Lyme and Zika Prevention” techniques in this post are are based primarily on information and recommendations from the CDC (Centers for Disease Control) and EPA (Environmental Protection Agency). E.g the CDC’s section on “Maximizing protection from mosquitoes and ticks:” But they are also based on Alison’s and my experience hiking long distances in hot, humid environments with high disease risk. Examples include the tropical jungles of South America—or spring in Shenandoah National Park (lots of Lyme!).

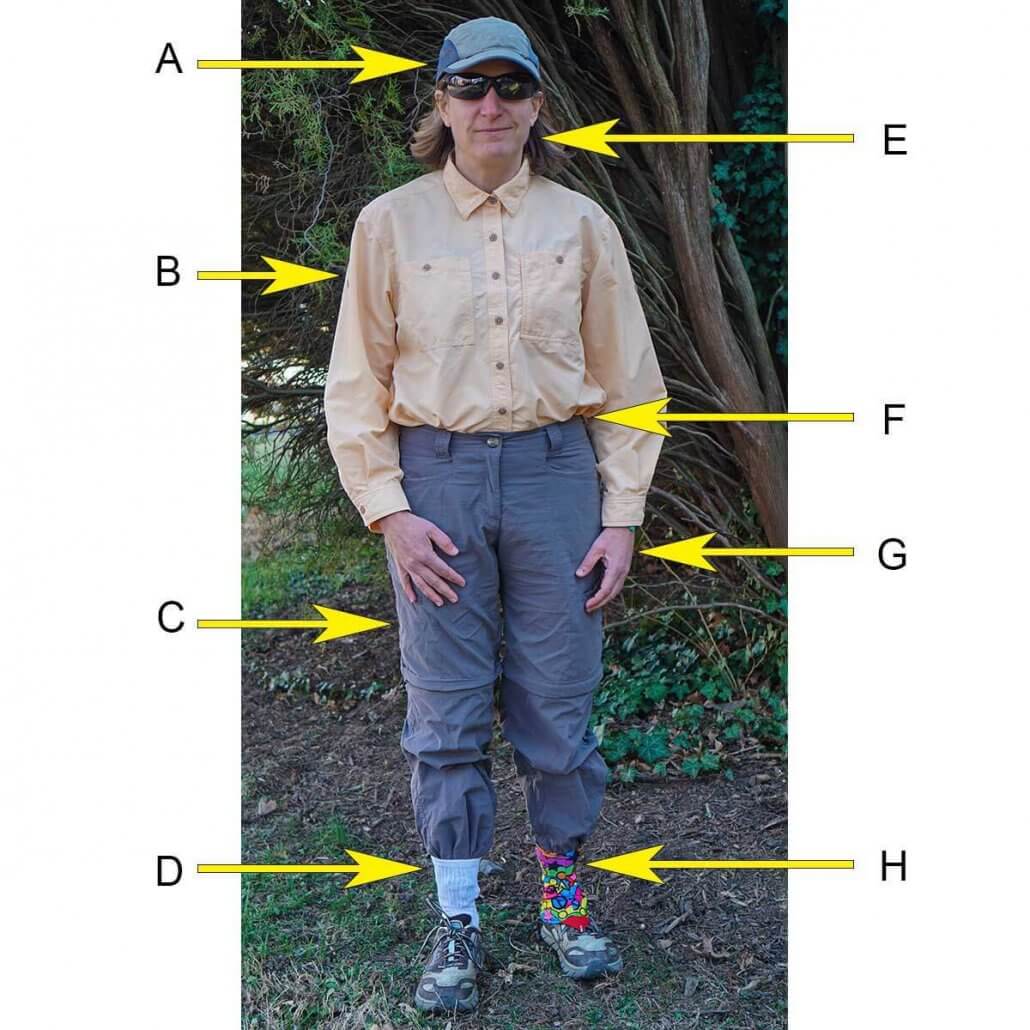

A short list of Clothing and Bug Protection (a cool set that you won’t overheat in)

Yes, the outfit might look slightly geeky (although bright gaiters spice things up). But having contracted Lyme disease on the AT, I can say without reservation it is an illness you never want!

for best viewing of this table on a mobile device, turn phone sideways (or view on a laptop or tablet)

| Item | Description | Comments | |

|---|---|---|---|

| E G | Bug repellent on face neck hands | Sawyer Picaridin lotion 14 hrs! Pocketable Picaridin 0.5 oz spray |

Lasts 14 hrs! No odor. Won’t melt plastic. Small, pocketable, easily applied. |

| A | Hat (repellent) | Exofficio Bugsaway Hat | Bug repellent for upper head area |

| B | Shirt hiking* | RailRiders Men’s Journeyman Shirt w Insect Shield & Women’s Oasis | Cool fabric, mesh side vents, sun protection, Lifetime insect repellent (vs. sprays 8-14 hrs) |

| Shirt (alt) | Exofficio Bugs Away Halo Long Sleeve Shirt Men’s and Women’s | Widely available: Campsaver and other sources like Amazon. Lifetime insect repellent. | |

| C | Pants hiking* | ExOfficio BugsAway Ziwa Pants Men’s and Women’s | Available in both Men’s and Women’s. Light, cool, sun protection. Lifetime insect repellent. |

| Pants (alt) | RailRiders Men’s Eco-Mesh Pant with Insect Shield | RailRiders pants have huge side vent on legs for cooling. Lifetime insect repellent. | |

| E G | Bug repellent on face neck hands | Sawyer Picaridin lotion 14 hrs! Pocketable Picaridin 0.5 oz spray |

Lasts 14 hrs! No odor. Won’t melt plastic. Small, pocketable, easily applied. |

| D | Physical Prot. | Tuck pants into socks | Prevents tick entry into pants. Stops pants legs from “gapping” and exposing ankle to mosquitos |

| F | Physical Prot. | Tuck shirt into Pants | Prevents tick entry into pants and lower shirt area. |

| H | Gaiters | Dirty Girl gaiters (fun colors!) or REI Co-op Activator Gaiters |

Seals pants against tick entry. No ankle gaps. Can be treated with permethrin spray. |

| H | Gaiter trap shoe (optional) |

Altra Lone Peak shoes or Altra Superior shoes |

Velcro “gaiter trap” permanently attached to heel of shoe. (adhesive ones that come with gaiters only work for a while) |

* You can treat your own clothing with Permethrin Spray (REI) or at Amazon This lasts for up to 6 weeks or 6 washings. (For comparison: factory treated clothing is good for up to 70 washings, essentially “life-time” use). Both clothing treatments far exceed the 8-14 hours of skin applied repellents like Picaridin and DEET. And they don’t require the time/attention needed to properly apply repellents to large areas of skin each day.

Picaridin – A New Repellent Better than DEET

Picaridin (lotion) lasts 40% longer than most DEET products and lacks the downsides of DEET. It has no odor and doesn’t melt plastics or degrade clothing. In Hand: Airline friendly 0.5 pump sprays, last 8 hours are small, pocketable and easily applied in the field. Right rear: Picaridin lotion lasts 14 hours, and can be repackaged into small 1 oz squeeze bottles.

Picaridin is a new (2005) “pepper-based” insect repellent that lasts up to 40% longer than most DEET products. And perhaps more important, it lacks many of the downsides of DEET. Picaridin has no odor and doesn’t melt plastics or degrade clothing. It is registered as safe and effective by the US EPA. More about Picaridin here

- Picaridin lotion at 20% concentration is effective for mosquitoes and ticks up to 14 hours. See: Insect Repellents: Use and Effectiveness (EPA)

- In comparison, DEET is effective against mosquitoes for up to 10-12 hours at moderate (~20 to 30%) concentrations. But for 10 hour effectiveness against ticks, DEET needs to be above 90% concentration vs. Picaridin’s 14 hours at 20%.

- Airline friendly 0.5 pump sprays (lasts 8 hrs) are small, pocketable and easily applied in the field.

- But Picaridin lotion is the champ, lasting 14 hours. (The lotion can be repackaged into a 1 oz squeeze bottle—this is our first choice when hiking.)

Important: Make sure you closely follow the directions for applying repellents, including knowing how long an application will last! Skin applied repellent effectiveness greatly depends how well and how often you apply it.

Treated tents and camp mosquito netting

Note: The EPA has also approved Sawyer permethrin spray as an insect repellent treatment for tents. As such, you may want to consider this option if you are in an area with high risk of disease and/or you are a person super concerned about ticks and mosquitoes. This spray treatment might be especially useful to treat the bug netting on the door(s) of your tent where insect entry would be most likely and where mosquitoes want to hang out. As always, follow the package directions to the letter!

- A National Institute for Health (NIH) study indicates that “Permethrin treatment of tents is an effective, inexpensive public health measure to reduce mosquito bites.”

- The CDC says: “[bug] nets are most effective when they are treated with a pyrethroid insecticide.”

3. What to do if you get a tick bite – per the US CDC

Use fine-tipped tweezers to grasp the tick as close to the skin’s surface as possible.

Pull upward with steady, even pressure. Don’t twist or jerk the tick; this can cause the mouth-parts to break off and remain in the skin. Avoid folklore remedies such as “painting” the tick with nail polish or petroleum jelly, or using heat to make the tick detach from the skin. Your goal is to remove the tick as quickly as possible–do not wait for it to detach.

- Here are the complete instructions for how to best remove the tick (and send it in for testing if you wish)

- In most cases, the tick must be attached for 36 to 48 hours* or more to transmit Lyme disease

[*Note: There may be no established minimum attachment time for Lyme transmission. Rather, This study from the National Institutes of Health suggests that the chance of Lyme transmission increases the longer the tick is attached, with no minimum time.] - Here are the Signs and Symptoms of Lyme Disease to look for

- And always check carefully for ticks each hiking day

“If you develop illness within a few weeks of a tick bite, see your health care provider right away.”

“Patients treated with appropriate antibiotics in the early stages of Lyme disease usually recover rapidly and completely.”

4. Non Chemical Ways to Reduce Bug Bites

While this section is non-chemical, its content is important and applicable to all methods to reduce bug bites, chemical and non-chemical.

Overview

- Non Treated, Bug Protective Clothing: Wear clothing that bugs can’t bite through and/or ticks can’t enter. There are some challenges here when hiking in warm weather.

- Where and When You Go: Be smart about where and what time of year you take your trips. (also has a short section on international travel)

- Where You Camp: If possible, camp in areas with few bugs (some nearby camps, just a few minutes away can be much better than others!)

- Shelter bug netting: Includes tips you may not know about using a tent or shelter with bug netting

a) Non Chemically Treated yet still Bug Protective Clothing

| The difficulty here is to: 1) prevent tick entry with seals on entry points for pants and shirt and 2) have clothing thick enough to stop mosquito bites. By the time you’ve met both criteria, your clothing is usually too hot and uncomfortable for warm weather hiking—the exact weather when bugs are prevalent & disease most likely. In summary, this is not an optimal warm weather option. It is listed here as an alternative for hikers who are leery of chemicals. |

I have used this non-chemical clothing system with success for some intense mosquito hatches in the Western Mountains in summer (Rockies/Sierras). It works well for camp, and is OK for moderate paced hiking as long as temps don’t climb into the 60’s or higher. The beauty of this system is that includes clothing I would normally bring on a hike (e.g. a windshirt/rain jacket and baselayer/hiking shirt).

for best viewing of this table on a mobile device, turn phone sideways (or view on a laptop or tablet)

| Item | Description | Comments | |

|---|---|---|---|

| A | Windshirt | Patagonia Houdini or most “windbreakers” |

Any windbreaker or rain jacket will work. When layered over a midweight baselayer, this provides decent protection against mosquito bites. Good for camp, but a hiking challenge in warm weather. |

| Baselayer | Capilene Midweight Top Ibex Indie Hoodie 1/4-Zip |

This is also my hiking shirt in cooler environments like the Western Mountains in Summer (Rockies/Sierras) | |

| B | Gloves | Glacier Glove fingerless fleece | Protection from bugs, but fingertips free for dexterity. |

| C | Pants hiking | REI Sahara convertible pants RailRiders X-Treme Adventure |

Need to be thick enough that mosquitoes can’t bite thru. Note: While these have worked well for me, I can’t say with 100% confidence that either of these pants are thick enough to prevent all mosquito bites. |

| D | Hat, ballcap | OR Sun Runner Hat | Scalp protect. Keeps netting off face. Any brimmed hat fine. |

| E | Bug-net | Sea to Summit Head Net | Non-chemically treated. OK for camp, but not fun to hike in. |

For hiking in warmer weather (e.g. AT in summer), one might need to find a single shirt (and pants) that meet your personal criteria for adequate protection from mosquitoes bites. (Since I use chemically treated clothing in warmer temps, I don’t have enough experience to recommend non-chemical pants and shirts.)

b) Where You Go: Be smart about where and when you take your trips

If you are through hiking the AT, you may not have wiggle room to avoid bugs. You’ll likely have to hike through the height of mosquito and tick season (mid-spring, summer, and early fall). In this case, you’ll just need to do your best to avoid bug bites. But most trips will likely have some good options to avoid the worst bugs. So do your research on what bugs are present and what times of the year they are most present/active. Then if possible, plan your trip to avoid the worst of the bugs. Here are some examples:

- We like to do much of our AT hiking in early spring and late fall when mosquito pressure is lower and there are hopefully fewer ticks. And winter on the AT is lovely with no mosquitoes and fewer ticks to worry about, and not a lot of people either!

- Mosquito pressure in Alaska is surprisingly low in August. But it is insane intense just a few months earlier around summer solstice (June 21).

- Alison and I take our kayaking trips in the everglades in January and February when mosquitoes are virtually non existent.

- And finally, where you camp (see below) and where you walk has an impact, especially with ticks. Wading through thick brush or grasses (e.g. an off trail bio break) in spring/summer on the East Coast will invite a greater chance of encountering ticks. Sticking to the grass free center of the trail helps.

Here are a few resources to help research bug and disease pressures for your trips

- For the United States: CDC Lyme Disease Maps, and Maps of Zika in the US

- International Travel: Look up your country in CDC’s Travelers Health Destinations List. Always do this in consultation with a travel health professional. The CDC recommends visiting your travel doctor (ideally, 4-6 weeks) before your trip to get vaccines or medicines you may need.

c) Where You Camp: If possible, camp in areas with fewer bugs

While it is unlikely that that you can avoid bugs completely, good campsite selection can greatly reduce the number of bugs in camp, even in areas with lots of bugs like Alaska in June. Sometimes a campsite only a few minutes walk away may have far fewer bugs.

- Where insects live: Camp away from boggy soggy areas areas with standing water.

- Avoid places obviously frequented by animals: Don’t camp along game trails or other places obviously frequented by animals like deer and rodents (especially white-footed mice the primary carrier of blacklegged ticks that transmit Lyme).

- Find wind: Try to camp in open areas that have a breeze which reduces the number of flying insects. An elevated area, like a bluff above a river or a small ridge is a good place. If you know the prevailing wind direction use it to your advantage. Note: Dense trees or brush stop wind, and therefore can harbor a lot of insects.

- Pay attention to elevation: In the mountains, biting insect hatches usually are most active at a particular altitude. Plan your day to camp above or below that altitude to reduce bug pressure.

- Final Check!: Before you commit to a camp, it’s good to stand around for 5-10 minutes and assess how bad the bugs are. If they are bad you can look for a better camp without having committed the time and effort to unpacking and setting up camp.

d) Use a tent or shelter with good mosquito netting

This is solution that is likely familiar to most people. And most of you already own a tent with good mosquito netting. But here are some things you may not know.

- You do not need a heavy tent for good protection from bugs. There are a number of light tents, TarpTents & other shelters that will protect two people for around 2 pounds (only 1 pound per person!). See my Recommended Tents, Tarps and other Shelters for some light but effective options.

- Hammocks with mosquito netting are also a good option. These are getting more popular on the AT, some are quite light. See more here: Hammock Camping Part I: Advantages & disadvantages versus ground systems

Tip: When entering your tent, take “a lap” away from your shelter before running back and jumping quickly through the door. By doing this you’ll likely shake the insects hovering around you, and therefore bring far fewer mosquitoes into the tent. After getting into the tent, do a search and destroy mission for the few bugs that may have tailgated in with you.