This post answers two questions. First, why the point and shoot camera is dead for hikers? And second, what are the best cameras for hiking now that the point and shoot camera is dead?

Why the Point and Shoot Camera is Dead for Hikers

The point and shoot (p/s) camera is being squeezed into the grave from two sides. 1) on the inexpensive* side by constantly improving smartphone cameras. And 2) on the more expensive side by very light mirrorless, interchangeable-lens cameras. If photography is a serious objective of your trip, their near “pro-level” performance justifies their cost/weight vs. carrying just your smartphone.

* smartphone cameras are “inexpensive/free,” in the sense that you likely own a smartphone, thus there is no additional cost and weight since most hikers and backpackers are already carrying their smartphone.

The Two Obvious Hiking Camera Options

1) You are satisfied with your smartphone camera

Therefore, a point and shoot (p/s) camera provides no additional benefit. The rapidly increasing capabilities, image quality (and video) of smartphone cameras are closing in on the performance of low to mid-range priced p/s cameras. Your current smartphone is essentially free* and no additional weight. Finally, you are likely an expert using your smartphone’s camera. It’s a perfectly valid option!

In good light smartphones take great pictures. In addition, there are a vast array of inexpensive accessories and apps/software to get the absolute best photos and video from your smartphone. Left JOBY GripTight Micro Stand. Right JOBY POV kit with bluetooth remote.

2) You want a camera that is significantly better than your smartphone

In this case you likely want better image quality, sharper lenses, an electronic viewfinder, more controls, etc. A p/s camera will not provide this! A light mirrorless, interchangeable-lens camera (mirrorless camera) will. In fact, mirrorless cameras are approaching “pro image quality” at a fraction of the cost and weight of many “pro” cameras. E.g. the Sony a6000/a6500 or Olympus EM-10 Mark II.

Class leading image quality for less weight: Sony a6000/a6500 camera with Sigma 30mm 1.4 DC DN Contemporary lens. This setup goes toe-to-toe with far heavier and more expensive APS-C (crop sensor) camera setups from Nikon and Canon.

Mirrorless Cameras are better “point and shoot” cameras than point and shoots

When you mount a light mirrorless camera on a quick release shoulder mount and put it in smart-auto mode, it’s faster and easier to use than a p/s camera. But you have all the benefits of interchangeable lenses and full camera control if you want. And of course, the image quality is in another league vs. a p/s camera.

For me, it’s all about the speed and ease of taking a photo. Since I changed to using the Peak Designs CapturePRO mounting system on the shoulder strap of my pack, I get 2 to 3 x more photos per trip. More than I ever got with a point and shoot camera in my pocket!

Note in the video how quickly and easily I put my pack on with my Sony a6000 mirrorless camera already attached to my shoulder strap with the Peak Designs CapturePRO. No camera spinning around and twisting up the shoulder strap.

The Bottom Line

If you want something significantly better than your smartphone camera a p/s is not sufficiently better to justify its cost and weight. On the other hand, a mirrorless camera is substantially better than a smartphone camera and therefore its cost and weight are justifiable. In addition, a mirrorless camera is far more versatile than a p/s (or even a 1″-type sensor camera). It is also an excellent general-purpose camera for use at home, nature photography with a long lens, for extended international travel (backpacking and non-backpacking), etc. This makes it a far better value than a p/s camera or even 1″-type sensor cameras like the Sony RX-100.

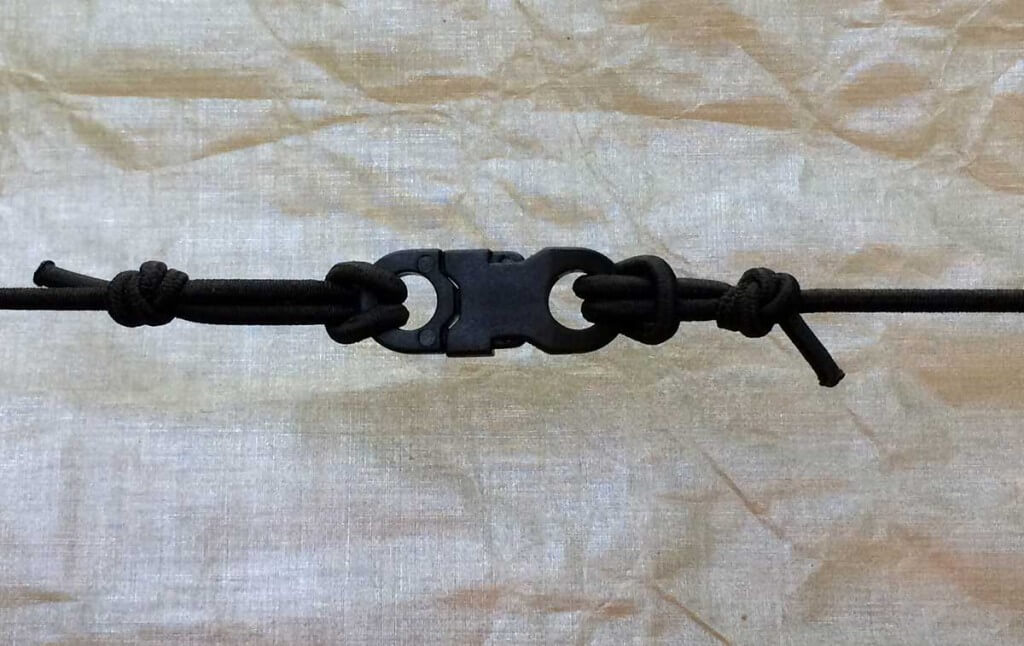

The full Sony a6000/a6500 kit: Peak Designs CapturePRO (mounts to backpack shoulder strap), Peak Designs Micro Plate (mounts to camera bottom), Pedco utra-pod II (small tripod), Sony NP-FW50 Battery, and Newer® Fish Bone quick release for tripod head.

What I Use Most of the Time

On most of my backpacking trips and on international travel, I carry both options:

- My iPhone 6 plus, and

- A light mirrorless a mirrorless camera, like a Sony a6000/a6500 or Olympus EM-10 Mark II

- Optional: when I need an environmentally sealed camera/lens system (dust and rain) I carry something like the Olympus OM-D EM-5 Mark II with 12-40 f/2.8 PRO lens.

Sony Lenses |

Olympus Lenses |

| Sigma 30mm f/1.4 Contemporary lens sharp as it gets! Sony SEL35F18 35mm f/1.8 sharp, fast, stabilized Sigma 19mm f2.8 DN low cost, light Sigma 30mm f2.8 DN sharp, low cost, light kit Sony 16-50mm f/3.5-F5.6 decent, low $, light |

Olympus 9-18mm f4.0-5.6 super wide, 5 oz! Olympus 12-40mm f/2.8 PRO very sharp, environmentally sealed Sigma 30mm f/1.4 prime. tack sharp, fast kit Olympus 14-42mm f/3.5-5.6 IIR decent, low $, light |

The Possible Exception to P/S Death“Point and shoot like,” 1-inch-type sensor cameras, e.g. the Sony RX-100 series do perform significantly better than the best smartphone cameras. For some their smaller size and lower weight vs. a mirrorless camera is a godsend. As such, they occupy a valid but narrow niche between smartphone cameras and mirrorless cameras. But note that their image quality not quite as good as similarly priced mirrorless cameras that may weigh only a few ounces more. They are too large and heavy to be truly “pocketable.” And finally, their single lens is only about 1/3 as sharp as the best interchangeable camera lenses for mirrorless cameras like the Sigma 30mm f/1.4 Contemporary lens. |

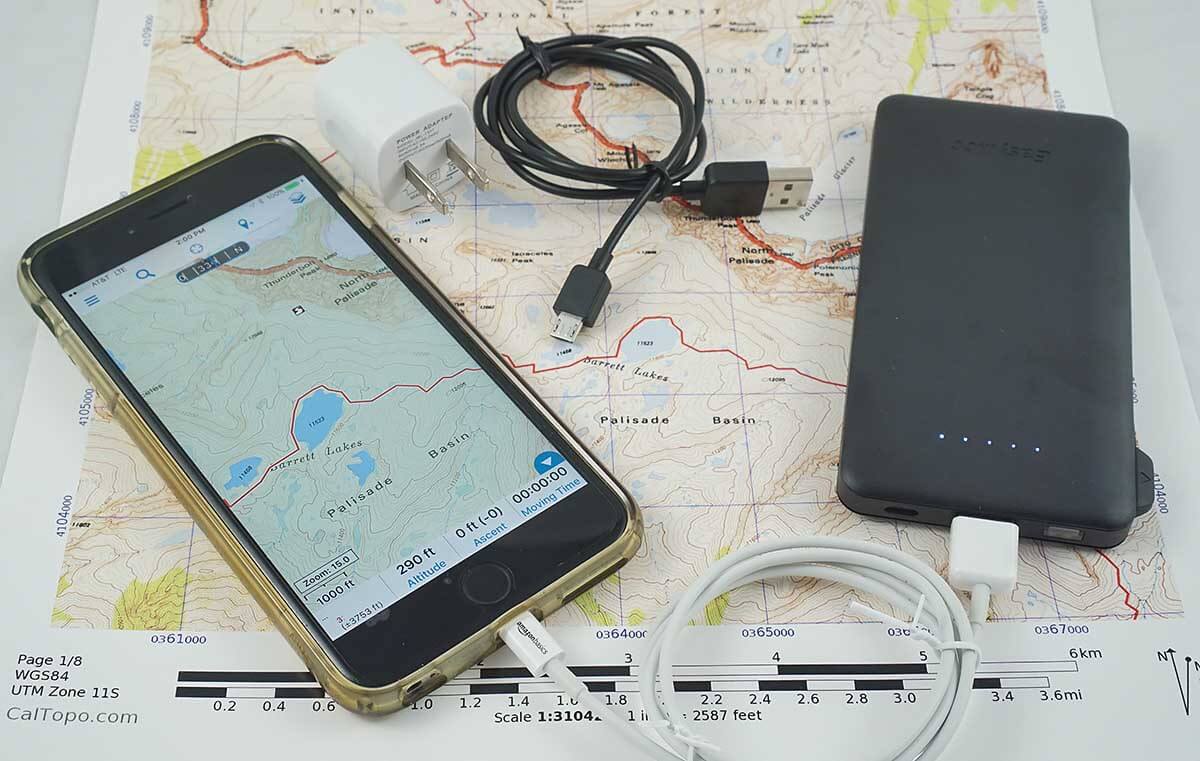

It’s critical safety precaution to make sure your electronics are always available for use. My three favorite lightweight and high capacity USB backup batteries are:

It’s critical safety precaution to make sure your electronics are always available for use. My three favorite lightweight and high capacity USB backup batteries are:

![Why we hike the AT. Glorious sunset from MacAfee Knob. [Photo Karan Girdhani]](https://www.adventurealan.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/Sunset-AT-Karan-G-1000.jpg)

Pack

Pack Warm Camp Clothing

Warm Camp Clothing

![A sudden opening in the clouds illuminates a lone tree and a small outcrop overlooking Loch Marie in Wester Ross. The summit of Slioch (left) is still shrouded in mist at midday. [Handheld with Olympus E-520 and stock 14-42mm f/3.5-5.6 Zuiko ED Zoom lens.] This photo looks great enlarged to 14x19.](https://www.adventurealan.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/scot_08-10-sm.jpg)

Also see

Also see